Your cart is currently empty!

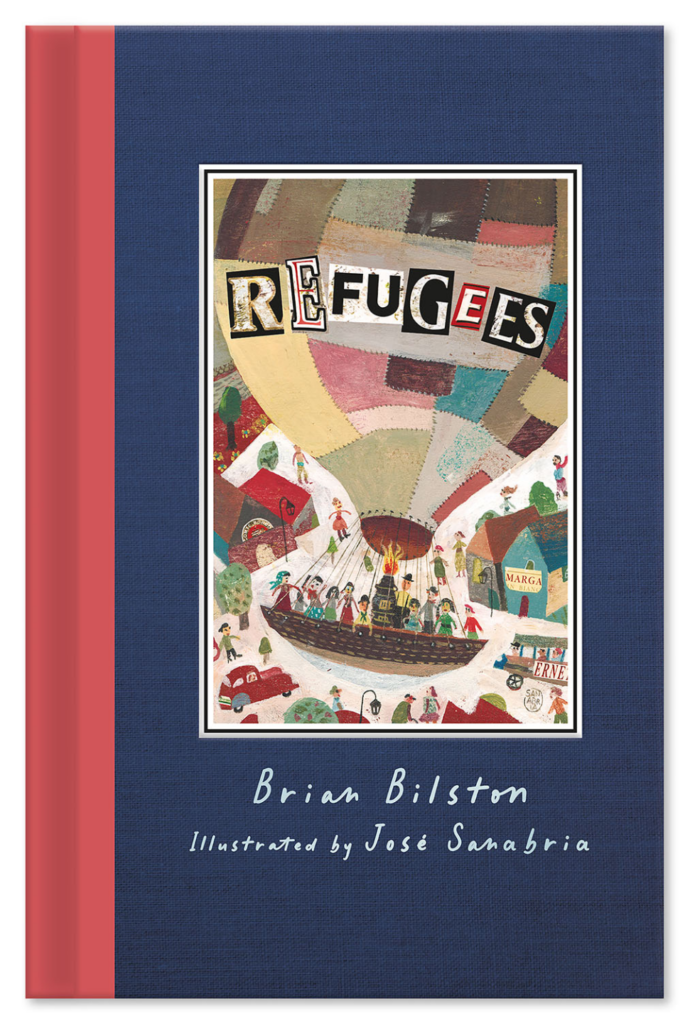

Refugees by Brian Bilston

Refugees Q&A with Brian Bilston

Refugee is a powerful word. One that conjures opposing emotions. For some it provokes feelings of fear and hate, for others the need for compassion, understanding, and empathy.

In this celebrated poem, “Refugees,” Brian Bilston tells both sides of the story by cleverly crafting a verse that can be read backward and forward to convey two opposing views.

Brian Bilston is often described as the “Poet Laureate of Twitter” (now X) and this much admired poem, perfectly accompanied by artwork from illustrator, Jose Sanabria, is a wonderful way to explore this emotive issue as you realise that it’s not just the words that have been reversed!

Author Q&A with Brian Bilston

Hi Paul (aka Brian),

Congratulations on your brilliant title, Refugees, publishing as a hardback. We’re already huge fan of the book and were delighted to feature the paperback version as part of our Refugee Week campaign. We cannot wait to delve into the book a little more with you in this author Q&A – thanks for taking part!

1. First of all, for those that are unfamiliar with Refugees, can you tell us a bit about the story?

It’s based on a reversible poem. Read it from top to bottom and you’re presented with a community which demonises refugees and doesn’t want anything to do with them. Read the poem from bottom to top and you have a community which welcomes refugees and recognises their fate could have been our own ‘should life have dealt a different hand’. The book brings these two different reactions together in a way that ends in a statement of support for refugees and what they go through, and how we need to support them.

2. You’re sometimes referred to as the Banksy of poetry. Why is that and what’s your opinion on this accolade?

I believe it’s because there are very few pictures available of me online which has led to a slight air of mystery about me. I don’t mind it too much – I do like a lot of Banksy’s work – although these days I am now out and about reading poems in front of audiences so I’m not sure the nickname still holds.

3. Did you always want to be a writer? What were your favourite books as a child?

I’ve always loved books and had hopes that one day I might manage to write one myself, but I never thought had the confidence to think I might be able to make a career of it. It’s a constant surprise to me that’s now what I do. When I was a child, I would read lots of different books – from adventure stories to football annuals. Some of the books which have always stayed with me are ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’ by CS Lewis, ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ by Roald Dahl, ‘I Am David’ by Ann Holm and ‘Stig of the Dump’ by Clive King.

4. Refugees is based on the poem that you wrote in 2016 which was extremely popular on social media. Were you surprised by the reaction to the poem?

Yes, hugely. I posted it on social media one weekday afternoon and had no idea it would go on to be so widely shared: I’d never had that kind of reaction to any poem I’d shared before! It still astonishes me how popular it remains, and it’s so wonderful when teachers get in touch and tell me they’ve been studying it with their class.

5. What gave you the idea for the poem to be turned into a picture book? Did you approach the publisher (Gemini Children’s Books) or they approach you?

The publisher approached me. I hadn’t thought about the poem working as a standalone book, but as soon as the idea was mooted, I knew it was a good one.

6. Jose Sanabria’s illustrations are captivating and allow the poem come to life. What was your impression of the illustrations when you first saw them? Did they match up to your idea of what they should be?

I loved them! Again, I had no preconceptions or particular expectations. None of my poems had ever been illustrated before. I was immediately struck by the vividness of the illustrations, the brightness of the colours, and the contrast between the menace of the black birds in the first half of the book with the faces of delight and joy in the second half.

7. The remarkable feature of the poem is of course the reversible nature in which it can be read. Were you concerned about how this would translate to a picture book?

A little. I was worried that the ‘trick’ of the poem might be harder to spot in picture book format but my fears were unfounded. I like the way the book also features the whole poem on its final page.

8. Our patron, Onjali Rauf, wrote the book The Boy at the Back of the Class after being affected by the refugee crisis and in particular the tragic death of Alan Kurdi. For you, was there a particular moment that resonated with you?

I was watching the news and a story came on about a boat carrying refugees across the Mediterranean. It had overturned, and many lives were lost. The pictures were heart-breaking. But it was seeing the reaction on social media to these daily tragedies which were unfolding right in front of us that made me want to write about it in some way. I was struck by how polarised the debate over the refugee crisis had become: how could these terrible stories of displacement, the tens of thousands of people driven from their homes every day by war or famine or poverty elicit such opposing reactions from the rest of the world? In particular, how could anyone see these images – of refugees drowning in the Mediterranean, say, or a mother weeping for her dead child – and not respond with compassion? But there were some; their indifference – and sometimes cruelty – was as shocking as the pictures on my television. All of that was to feed into my poem.

9. In your opinion, what can young people in this country do to make a difference?

I think it’s important to treat other people as you would wish to be treated yourself, and always look for the good in others. I feel that young people are often far better at doing this then adults: what a positive difference it could make if we could carry those attitudes through our adult life, too. It gives me great hope for the future when teachers who’ve been studying ‘Refugees’ tell me how outraged their students are when they first read the poem from top to bottom – and so they should be! Young people have much to teach the rest of us when it comes to empathy, kindness and compassion.

10. You’re most famously a poet but have written a novel: Diary of a Somebody (Picador, 2019), which was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel award. Would you ever consider writing a novel for children?

I have thought about it before but haven’t got very far. I keep getting distracted by other things. Also, writing poems is very moreish.

11. You continue to receive great praise for your work and have even been described as the ‘unofficial poet laureate of Twitter’. What have been your proudest moments as a writer and what advice would you give to any young person wanting to write?

Two moments in my writing career have really stood out: the feeling of achievement (and joy!) when I held my first collection of poetry in my hand for the first time; and the time I heard from a teacher that she had used ‘Refugees’ with her class, and one boy had declared me ‘a legend’.

In terms of advice for wannabe writers, I have two golden rules: 1) read widely – you’ll be amazed by all the writing tips and tricks you’ll pick up along the waywithout realising; 2) keep at it – like most things, practice makes perfect (or makes less imperfect), so write regularly and often, and 3) don’t follow rules.

12. We have a tradition of asking our guests to describe their book in three words – how would you describe Refugees?

Bridges not walls.

Blog post by

Rob McCann